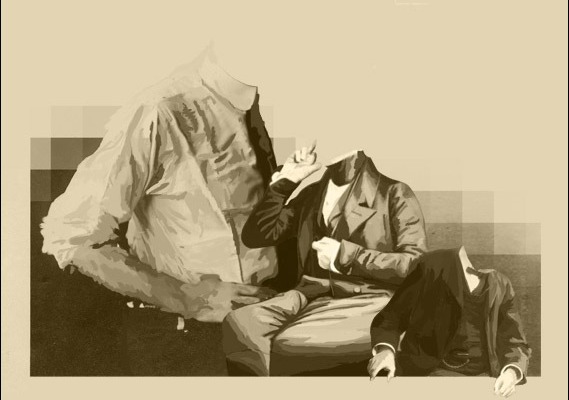

Charles Bukowski might be the literary equivalent of Marmite i.e. you love him or you hate him. I imagine very few people ride the fence on this one. For example, before I read any of his work, a good friend of mine, who gives me plenty of great reading recommendations, said something like: “Bukowski’s not a good writer; he’s just a drunk.” When I was getting my MA, one of my instructor’s said something like “I hate Bukowski, probably because I don’t want to believe that men actually treat women that way”. On the other hand, I had two different people who liked Bukowski so much, that they commissioned me to paint portraits of him. Despite hearing about him from all of these people, I hadn’t actually read any Charles Bukowski until I had a chance encounter with an alcoholic (which the author himself might’ve appreciated).

The drunk in question had well-meaning parents who wanted to get him a gift, but didn’t want to give him money because they knew he’d piss it away, so they gave him books. He proceeded to sell those books to his fellow MA students at the pub and use the money to buy beer. Now, I’m not proud of being an enabler, but when this gentleman begged me to buy his copy of Post Office at a reasonable discount, I went along with it…and thoroughly enjoyed the book. Turns out old Buke wasn’t just a drunk after all.

Despite cranking out a prolific amount of poetry and short fiction, Charles Bukowski only wrote seven novels and I think they’re fairly easy to rank. Or, at least six of them can be ranked together and then there’s one odd ball out in left field, which I’ll come to later.

Ham on Rye is easily the greatest literary achievement of the Bukowski’s novels because it brings his humanity into focus. The semi-autobiographical story deals so intimately and honestly with his brutal childhood that it gives readers a chance to sympathise with him before he becomes the sloppy misanthropic misogynist of his later works.

On the other hand, Post Office does less to get the reader emotionally involved and more to entertain them. With the exception of a few unscrupulous episodes that cross the line, this novel is probably the most fun to read.

Factotum deals with a lot of the same type of crappy job/pitiful existence anecdotes as Post Office, but it lacks the same sense of coherence. If you like the vibe of Post Office and you want more of the same, you’ll enjoy Factotum, but it doesn’t have much of a story arch.

In Hollywood, Bukowski manages to recapture the strong story arch of Post Office as well as it’s sense of humour. All in all, it’s a better novel than Factotum, but in it, the main character has come so far along his trajectory, it’s hard to believe it’s the same person. If you like the ‘low-life’ aspect of the earlier novels, you might be slightly disillusioned by this story of how those hi jinx were ultimately made into a movie. On the other hand, it’s a nicely surreal capstone to one of the most unbelievable manifestations of the American dream. Immigrant comes to the USA, lives in the gutter, gains a cult following, ends up on the silver screen.

At the far end of the spectrum, Women is probably the worst of his semi-autobiographical novels or, at the very least, it’s the hardest to read without constantly cringing. In a documentary I watched, Bukowski’s last wife explained that she wasn’t thrilled when she read it and you can hardly blame her. I can’t imagine most woment would be thrilled by it.

With 6 out of the 7 novels behind us, that just leaves the odd ball: Pulp. This is Bukowski’s only non-autobiographical work and his only stab at genre fiction. To some extent, it suffers on both accounts. It’s easy to read it and think, this isn’t a great Bukowski novel or a great detective novel. But, I’d contend that it was never meant to be. I think Bukowski was intentionally lampooning the detective genre, as well as his own body of work. Viewed in that light, this self-consciously weak book actually comes across as kind of clever. And when you consider the ending in the light of the fact that he basically finished it on his death bed, it’s also kind of bittersweet.

So, if you’re interested in Bukowski, start with Ham on Rye or Post Office. If you like Post Office, you’ll probably like Factotum. If you like Ham on Rye, you might be interested to read Hollywood to see how the wild ride of his life starts and ends. If you’re at all uncomfortable with misogynism, skip Women altogether. And, unless you’re trying to work your way through the whole collection like I did, you can probably give Pulp a miss as well.

For my next author review, I think I’ll take a shot at an Italian stallion: Alessandro Barrico.

Ham on Rye

Post Office

Hollywood

Factotum

Pulp

Women